- Posted on : October 6, 2013

- Posted by : Tom Fletcher

Shen Weiqin was Diplomatic Adviser to Emperor Qin Er Shi during the Qin dynasty. It was probably a pretty cushy job, with steady access to the pleasures of the royal court, a fair amount of arduous but interesting travel, and long periods of relative peace in which to study and entertain. He knew his master’s mind, and was well able to play the role of what we now call a sherpa, the key adviser who helps the leader prepare for diplomatic summits. The sherpa’s assistant is called the yak, a metaphor that would have meant something to His Excellency Shen.

Shen must have anticipated a routine month’s work as he set out for the Congress of the Tribes in Xianyang in 208 BC. The Emperor’s armies had defeated the Chu tribe, burying alive those who surrendered. This left the field open for a strong peace treaty giving Qin increased taxes and land rights. Straightforward business for Shen, who by this time had negotiated three such deals with defeated clans. Making peace is easier when you have shown you can make war. To paraphrase Roosevelt many centuries later, ‘speak softly and carry a big scimitar’.

But Shen was to get a shock. The diplomats representing the Chu tribe had developed a new means of passing messages quickly, involving the positioning of rested horses along key trade routes. So they had gathered intelligence of an uprising in the West and of disquiet within Qin’s ranks caused by the despotism of his favourite adviser, the eunuch Zhao Gao. They were able to use this information to hold out for a better deal.

Shen returned to his master to report the bad news. His Emperor had demonstrated his lack of mercy the previous year when he tricked his elder brother (the rightful heir to the dynasty) into committing suicide. He decided to punish poor execution with execution. Shen was tied to a wooden frame and ‘slow sliced’, a particularly gruesome demise involving the methodical removal according of 999 body parts in random order as drawn from a hat: death by a thousand cuts, give or take. The process, ‘lingchi’, literally means ‘ascending a mountain slowly’, a metaphor for his pre summit diplomacy that Shen was presumably unable to relish. His diplomatic failure was classified as treason, so no opium was administered to ease the pain.

It is not recorded at what point in the three day process Shen passed away, but his grisly exit provided evidence for Lu You, one of history’s first human rights activists, to argue in 1198 for the abolition of the practise, which is how we know about it. Again, probably no consolation to poor old Shen.

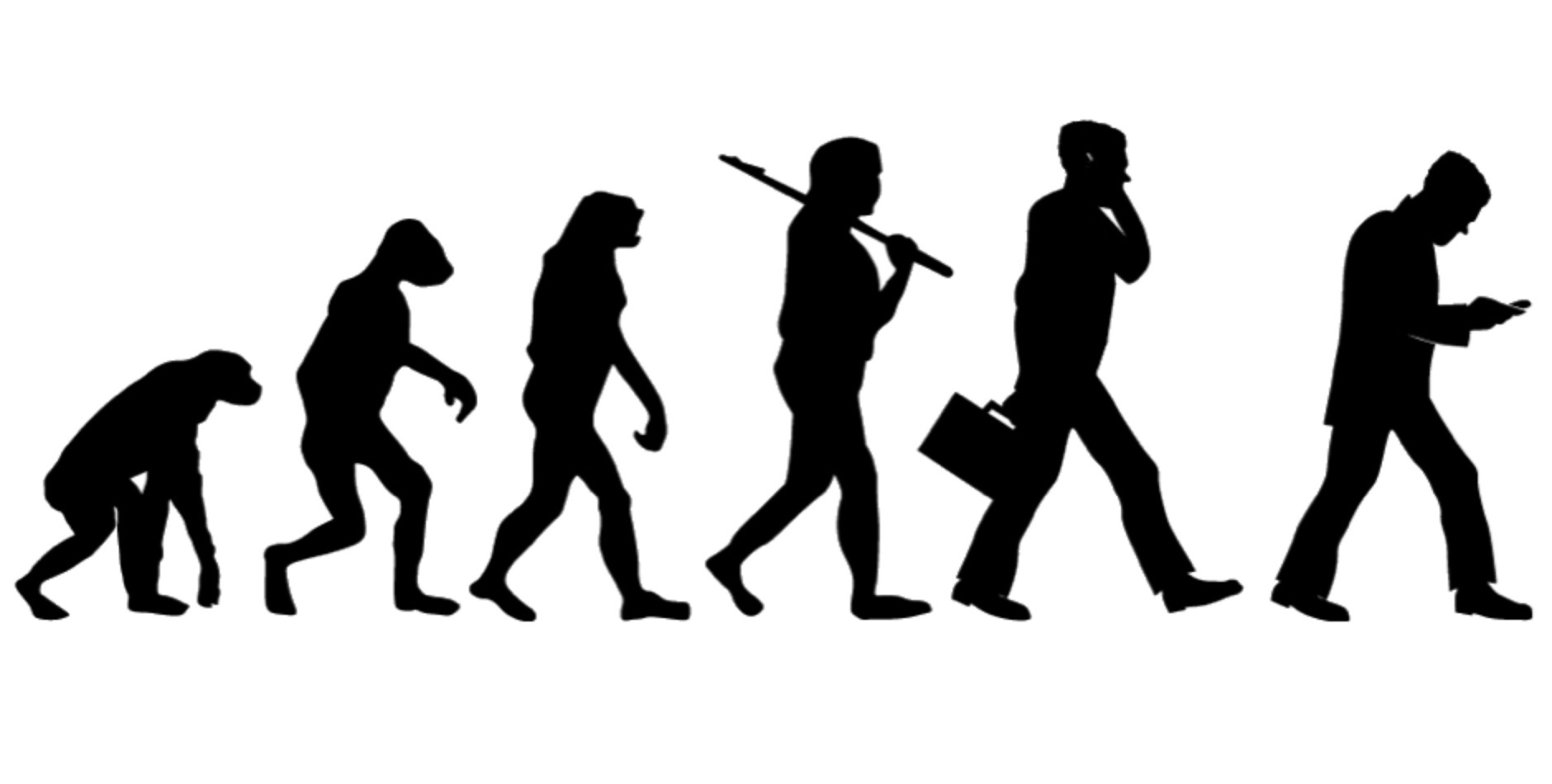

Shen discovered that diplomacy is Darwinian – its practitioners have to evolve or die.

Today’s poor performance procedures are more time consuming if less robust than Qin’s. But given that the alternative to peacemaking is often war, our failures also have consequences. When the way the world communicates changes, so must its diplomats. We transformed our business when sea routes opened up, when empires rose and fell, the telephone came along. Some said you could replace diplomats with the fax. We saw off the fax, and – in recent years – the telegram. Now we have to prove that you can’t replace diplomats with Wikipedia and Skype. Or even Twitter.